Hemoglobin (Hb) is an iron-containing metalloprotein found abundantly in the red blood cells of virtually all vertebrates. It is often hailed as the “life-sustaining molecule” for its indispensable role in respiration. This intricate protein is responsible for the critical task of transporting oxygen from the lungs to every tissue in the body and facilitating the return of carbon dioxide for excretion. Understanding its function, the elegant mechanisms that govern its behavior, and the paramount importance of its clinical measurement provides a window into human health and disease.

Function and Mechanism: A Masterpiece of Molecular Engineering

The primary function of hemoglobin is gas transport. However, it does not perform this duty like a simple, passive sponge. Its efficiency stems from a sophisticated structural design and dynamic regulatory mechanisms.

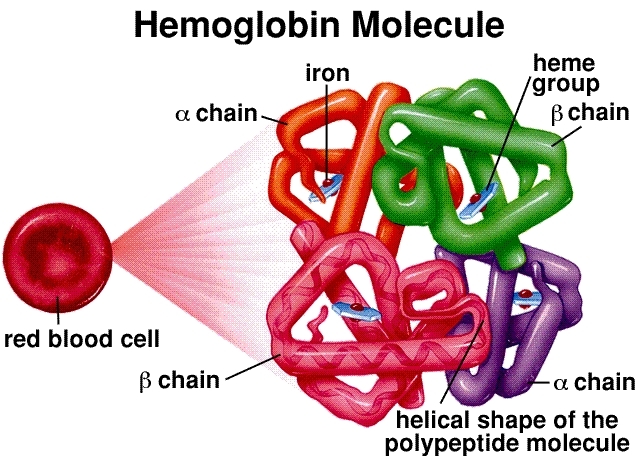

Molecular Structure: Hemoglobin is a tetramer, composed of four globin protein chains (two alpha and two beta in adults). Each chain is associated with a heme group, a complex ring structure with a central iron atom (Fe²⁺). This iron atom is the actual binding site for an oxygen molecule (O₂). A single hemoglobin molecule can therefore carry a maximum of four oxygen molecules.

Cooperative Binding and the Sigmoidal Curve: This is the cornerstone of hemoglobin’s efficiency. When the first oxygen molecule binds to a heme group in the lungs (where oxygen concentration is high), it induces a conformational change in the entire hemoglobin structure. This change makes it easier for the subsequent two oxygen molecules to bind. The final fourth oxygen molecule binds with the greatest ease. This “cooperative” interaction results in the characteristic sigmoidal (S-shaped) oxygen dissociation curve. This S-shape is crucial—it means that in the oxygen-rich environment of the lungs, hemoglobin becomes saturated rapidly, but in the oxygen-poor tissues, it can release a large amount of oxygen with only a small drop in pressure.

Allosteric Regulation: Hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen is not fixed; it is finely tuned by the metabolic needs of the tissues. This is achieved through allosteric effectors:

The Bohr Effect: In active tissues, high metabolic activity produces carbon dioxide (CO₂) and acid (H⁺ ions). Hemoglobin senses this chemical environment and responds by decreasing its affinity for oxygen, prompting a more generous release of O₂ exactly where it is needed most.

2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG): This compound, produced in red blood cells, binds to hemoglobin and stabilizes its deoxygenated state, further promoting oxygen release. Levels of 2,3-BPG increase in chronic hypoxic conditions, such as at high altitudes, to enhance oxygen delivery.

Carbon Dioxide Transport: Hemoglobin also plays a vital role in CO₂transport. A small but significant portion of CO₂binds directly to the globin chains, forming carbaminohemoglobin. Furthermore, by buffering H⁺ions, hemoglobin facilitates the transport of the majority of CO₂ as bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) in the plasma.

The Critical Importance of Hemoglobin Testing

Given hemoglobin’s central role, measuring its concentration and assessing its quality is a fundamental pillar of modern medicine. A hemoglobin test, often part of a Complete Blood Count (CBC), is one of the most commonly ordered clinical investigations. Its importance cannot be overstated for the following reasons:

Monitoring Disease Progression and Treatment:

For patients diagnosed with anemia, serial hemoglobin measurements are essential to monitor the effectiveness of treatment, such as iron supplementation, and to track the progression of underlying chronic diseases like kidney failure or cancer.

Detection of Hemoglobinopathies:

Specialized hemoglobin tests, such as hemoglobin electrophoresis, are used to diagnose inherited genetic disorders affecting hemoglobin structure or production. The most common examples are Sickle Cell Disease (caused by a faulty HbS variant) and Thalassemia. Early detection is vital for management and genetic counseling.

Assessment of Polycythemia:

An abnormally high hemoglobin level can indicate polycythemia, a condition where the body produces too many red blood cells. This can be a primary bone marrow disorder or a secondary response to chronic hypoxia (e.g., in lung disease or at high altitudes), and it carries a risk of thrombosis.

Screening and General Health Assessment:Hemoglobin testing is a routine part of prenatal care, pre-surgical check-ups, and general wellness exams. It serves as a broad indicator of overall health and nutritional status.

Diabetes Management:While not the standard hemoglobin, the Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c) test measures how much glucose has become attached to hemoglobin. It reflects the average blood sugar levels over the past 2-3 months and is the gold standard for long-term glycemic control in diabetic patients.

Conclusion

Hemoglobin is far more than a simple oxygen carrier. It is a molecular machine of exquisite design, employing cooperative binding and allosteric regulation to optimize oxygen delivery in response to the body’s dynamic needs. Consequently, the clinical measurement of hemoglobin is not just a number on a lab report; it is a powerful, non-invasive diagnostic and monitoring tool. It provides an indispensable snapshot of a person’s hematological and overall health, enabling the diagnosis of life-altering conditions, the monitoring of chronic diseases, and the preservation of public health. Understanding both its biological genius and its clinical significance underscores why this humble protein remains a cornerstone of physiological and medical science.

Post time: Oct-17-2025